Pentagon Papers

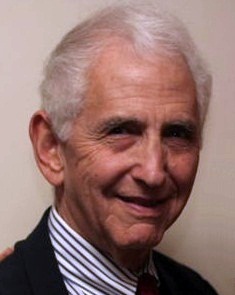

The Pentagon Papers is the informal title of the Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force, a US Defense Department study of the diplomatic and military history of the United States involvement in the Vietnam War from 1945 to 1968. A policy analyst and historian who contributed to the project, Daniel Ellsberg, leaked documents to The New York Times, who published the history report as The Pentagon Papers, in 1971.[1][2]

The chronologic, narrative history of The Pentagon Papers indicates that the U.S. had secretly widened the range and scope of provocative attacks against Vietnam, such as coastal raids on North Vietnam and Marine Corps attacks in South Vietnam, which yielded the Gulf of Tonkin Incident (2 August 1964) and the start of the American War against Vietnam. After the publishing of The Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg initially was accused of the crimes of criminal conspiracy, espionage, and theft of government property, which the prosecutors dismissed upon learning that President Nixon (1969–1974) had ordered the White House Special Investigations Unit (White House Plumbers) to assassinate the character of Daniel Ellsberg in effort to void his political credibility and that of The Pentagon Papers history.[3][4]

Contents

In 1967, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (r. 1961–1968) created the Vietnam Study Task Force to write an “encyclopedic history of the Vietnam War”[5] for government historians to advise future US presidents and prevent the types of errors of foreign policy that involved the US in an Asian civil war;[6] yet McNamara did not inform Pres. Lyndon Johnson (r. 1963–1969) or Secretary of State Dean Rusk (r. 1961–19690) about having commissioned the Pentagon for a diplomatic and military history of US involvement in the country of Vietnam.[5] McNamara assigned Assistant Secretary of Defense John McNaughton with the editorial remit to assemble the pertinent documents and deliver a complete historical report in three months’ time.[5][7] In the event, assistant defense secretary McNaughton was killed in an aeroplane crash in June 1967, but the Vietnam Study Task Force continued the history project, as directed by Leslie H. Gelb, director of policy planning at the Pentagon.[5]

The Vietnam Study Task Force comprised thirty-six foreign policy analysts (military officers, academic historians, civilians) who compiled and wrote the chronological history of American politico-military involvement in the domestic politics of Vietnam.[5] The collective authorship of The Pentagon Papers includes Daniel Ellsberg, Morton Halperin,[7] and Paul Warnke,[8] Paul F. Gorman,[9] John Galvin,[10][11][7] and the historian Melvin Gurtov, the economists Hans Heymann and Richard Moorstein, and Richard Holbrooke.[12][7][13] Moreover, the historical Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force was kept secret from the National Security Advisor Walt Rostow.[14][7] The editorial work of the Vietnam Study Task Force produced forty-seven volumes that answered defense secretary McNamara's one hundred questions about the United States’ failure to directly influence the socio-economic politics of the Republic of Vietnam, such as: (i) “How confident can we be about body counts of the enemy?” (ii) “Were programs to pacify the Vietnamese countryside working?” (iii) “What was the basis of President Johnson's credibility gap?” (iv) “Was Ho Chi Minh an Asian Tito?” and (v) “Did the U.S. violate the Geneva Accords on Indochina?”[7]

In February 1968, McNamara quit as secretary of defense and was succeeded by Clark Clifford (r. 1968–1969), who received the Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force on 5 January 1969, in forty-seven volumes;[15][7] 3,000 pages of historical analysis and 4,000 pages of cited government documents, all classified Top Secret sensitive material.[14][16]

Organization and subject

The Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force, informally The Pentagon papers (1971), is in forty-seven volumes thus organized:[17]

I. Vietnam and the U.S., 1940–1950 (1 Vol.)

- A. U.S. Policy, 1940–50

- B. The Character and Power of the Viet Minh

- C. Ho Chi Minh: Asian Tito?

II. U.S. Involvement in the Franco–Viet Minh War, 1950–1954 (1 Vol.)

- A. U.S., France and Vietnamese Nationalism

- B. Toward a Negotiated Settlement

III. The Geneva Accords (1 Vol.)

- A. U.S. Military Planning and Diplomatic Maneuver

- B. Role and Obligations of State of Vietnam

- C. Viet Minh Position and Sino–Soviet Strategy

- D. The Intent of the Geneva Accords

IV. Evolution of the War (26 Vols.)

- A. U.S. MAP for Diem: The Eisenhower Commitments, 1954–1960 (5 Vols.)

- 1. NATO and SEATO: A Comparison

- 2. Aid for France in Indochina, 1950–54

- 3. U.S. and France's Withdrawal from Vietnam, 1954–56

- 4. U.S. Training of Vietnamese National Army, 1954–59

- 5. Origins of the Insurgency

- B. Counterinsurgency: The Kennedy Commitments, 1961–1963 (5 Vols.)

- 1. The Kennedy Commitments and Programs, 1961

- 2. Strategic Hamlet Program, 1961–63

- 3. The Advisory Build-up, 1961–67

- 4. Phased Withdrawal of U.S. Forces in Vietnam, 1962–64

- 5. The Overthrow of Ngo Dinh Diem, May–Nov. 1963

- C. Direct Action: The Johnson Commitments, 1964–1968 (16 Vols.)

- 1. U.S. Programs in South Vietnam, November 1963–April 1965: NSAM 273 – NSAM 288 – Honolulu

- 2. Military Pressures Against NVN (3 Vols.)

- a. February–June 1964

- b. July–October 1964

- c. November–December 1964

- 3. Rolling Thunder Program Begins: January–June 1965

- 4. Marine Combat Units Go to DaNang, March 1965

- 5. Phase I in the Build-Up of U.S. Forces: March–July 1965

- 6. U.S. Ground Strategy and Force Deployments: 1965–1967 (3 Vols.)

- a. Volume I: Phase II, Program 3, Program 4

- b. Volume II: Program 5

- c. Volume III: Program 6

- 7. Air War in the North: 1965–1968 (2 Vols)

- a. Volume I

- b. Volume II

- 8. Re-emphasis on Pacification: 1965–1967

- 9. U.S.–GVN Relations (2 Vols.)

- a. Volume 1: December 1963 – June 1965

- b. Volume 2: July 1965 – December 1967

- 10. Statistical Survey of the War, North and South: 1965–1967

V. Justification of the War (11 Vols.)

- A. Public Statements (2 Vols.)

- Volume I: A – The Truman Administration

- B – The Eisenhower Administration

- C – The Kennedy Administration

- Volume II: D – The Johnson Administration

- Volume I: A – The Truman Administration

- B. Internal Documents (9 Vols.)

- 1. The Roosevelt Administration

- 2. The Truman Administration: (2 Vols.)

- a. Volume I: 1945–1949

- b. Volume II: 1950–1952

- 3. The Eisenhower Administration: (4 Vols.)

- a. Volume I: 1953

- b. Volume II: 1954–Geneva

- c. Volume III: Geneva Accords – 15 March 1956

- d. Volume IV: 1956 French Withdrawal – 1960

- 4. The Kennedy Administration (2 Vols.)

- Book I

- Book II

VI. Settlement of the Conflict (6 Vols.)

- A. Negotiations, 1965–67: The Public Record

- B. Negotiations, 1965–67: Announced Position Statements

- C. Histories of Contacts (4 Vols.)

- 1. 1965–1966

- 2. Polish Track

- 3. Moscow–London Track

- 4. 1967–1968

US Containment of China

Despite Pres. Johnson’s claim to the American public that the war against North Vietnam and the Viet Cong in South Vietnam would realize an “independent, non–Communist South Vietnam”, in private, a contradictory memorandum (January 1965) to Pres. Johnson, by assistant secretary of defense John McNaughton said that the true, geopolitical purpose of the US war in Vietnam was “not to help friend, but to contain China”.[18][19][20] Moreover, in a memorandum (3 Nov. 1965) to Pres. Johnson, defense secretary McNamara communicated the geopolitical rationale for the “major policy decisions with respect to our course of action in Vietnam”, especially Operation Rolling Thunder (1965–1968), the continual aerial bombardment of North Vietnam, begun by the US Air Force in early 1965:

The February decision to bomb North Vietnam and the July approval of Phase I deployments make sense only if they are in support of a long-run United States policy to contain China.[21]

To justify a US invasion and a land war in Vietnam, US defense secretary McNamara said that the People’s Republic of China was an imperialist power that would ultimately establish a regional hegemony that would “organize all of Asia” against the United States:

China — like [Imperial] Germany in 1917, like [Nazi] Germany in the West and [Imperial] Japan in the East in the late ’30s, and like the USSR in 1947 — looms as a major power threatening to undercut our importance and effectiveness in the world, and, more remotely, but more menacingly, to organize all of Asia against us.[21]

To explain the long-run, American foreign policy for the anti-communist containment of China by way of geopolitical isolation, defense secretary McNamara said: “There are three fronts to a long-run effort to contain China: (i) the Japan–Korea front; (ii) the India–Pakistan front; and (iii) the Southeast Asia front”;[21] however, McNamara admitted that the geopolitical and military containment of Communist China would require a land war in Vietnam.[21]

The US in Vietnam

After 1945, the involvement of the U.S. government to the political, socio-economic, and military affairs of Vietnam was by way of military advisors who trained the military and police forces of South Vietnam:

- The Truman government (1945–1953) supplied American matériel to French Indochina to fight the First Indochina War (1946–1959) against the Communist Viet Minh (League for the Independence of Vietnam).[22]

- The Eisenhower government (1953–1961) thwarted the vote (July 1956) for the territorial reunification of Vietnam agreed in the Geneva Conference (1954) by the US publicly supporting the existence of the new country of the “Republic of Vietnam” in the south of Vietnam, whilst secretly waging guerrilla war against North Vietnam.[22]

- The Kennedy government (1961–1963) changed the foreign policy towards Vietnam from a limited gamble in geopolitics to a broad commitment to bear the burden of building a new nation in Asia.[22]

- The Johnson government (1963–1969) waged secret war against North Vietnam in effort to provoke “a Communist invasion” of the Republic of Vietnam.[22]

US sponsorship of president Diem

To realize the geopolitical containment of Communist China, the US gave $28.40 million dollars of matériel to the Diem government to strengthen the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (1955–1975). To the end of creating politically loyal armed forces, US military advisors trained 32,000 men from the Civil Guard into the South Vietnamese Regional Force in the political hope that the American-trained men would withstand the Viet Communists’ ideological appeals to Viet nationalism and military recruitment into the Viet Cong.[23] In part IV B, “Counterinsurgency: The Kennedy Commitments, 1961–1963”, The Pentagon Papers report that the United States’ was politically obliged to support the Republic of Vietnam because the US created the country of “South Vietnam” in 1949:

We must note that [the Republic] of South Vietnam (unlike any of the other countries in Southeast Asia) was essentially the creation of the United States.[23]

The American establishment of the Republic of Vietnam in the south of Vietnam, allowed the OSS case officer Edward Lansdale to participate in the creation, selection, and the establishment of the politico-military régime of Pres. Diem in South Vietnam — and the continual US sponsorship of South Vietnam after the government of Diem. In a memorandum (1961) about the client state leader Diem, Lansdale said: “We [the US] must support Ngo Dinh Diem until another strong executive can replace him legally.”[23] The sub-section “Special American Commitment to Vietnam” outlines the Western geopolitics that determined the presence of the US in Asia, especially in the Republic of Vietnam:

- Without U.S. support [Ngo Dinh] Diem almost certainly could not have consolidated his hold on the South during 1955 and 1956.

- Without the threat of U.S. intervention, South Vietnam could not have refused to even discuss the elections called for in 1956 under the Geneva settlement without being immediately overrun by the Viet Minh armies.

- Without U.S. aid in the years following, the Diem régime certainly, and an independent South Vietnam almost as certainly, could not have survived.[23]

US deposition of president Diem

By the year 1963, President Ngô Đình Diệm’s political independence from his American advisors (CIA and military) proved inflexible and the US then ceased foreign aid to his government and sought a replacement president-of-Vietnam among the military establishment of South Vietnam. On 23 August 1963, CIA case officer Lucien Conein met with some generals of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) to plan the 1963 South Vietnamese coup d’état to depose Pres. Diem (r. 1955–1963), as the head of government of the Republic of Vietnam, in November 1963;[24] The Pentagon Papers report that:

For the military coup d’État against Ngo Dinh Diem, the U.S. must accept its full share of responsibility. Beginning in August 1963, we variously authorized, sanctioned, and encouraged the coup efforts of the Vietnamese generals and offered full support for a successor government.

In October we cut off aid to Diem in a direct rebuff, giving a green light to the generals. We maintained clandestine contact with them throughout the planning and execution of the coup and sought to review their operational plans and proposed new government.

Thus, as the nine-year rule of Diem came to a bloody end, our complicity in his overthrow heightened our responsibilities and our commitment in an essentially leaderless Vietnam.[25]

Provoking a war

To provoke open warfare between the Republic of Vietnam and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Director of Central Intelligence, John A. McCone (r. 1961–1965), proposed three categories of open and secret military actions in Laos and North Vietnam, and against the Vietcong guerrillas in the south of Vietnam:

- Category 1 — Operation Farmgate (1916–1963) secret aerial attacks against Viet Cong logistics by the Republic of Vietnam Air Force and the US Air Force.[26]

- Category 2 — Cross-border attacks against Viet Cong supply depots by ARVN and US military advisors.[26]

- Category 3 — Aerial bombing of targets in North Vietnam by unmarked aeroplanes crewed and flown by the air force of South Vietnam.[26]

As an intelligence officer, McCone informed Pres. Johnson that such covert warfare might not escalate to open warfare between north and south Vietnam because the “fear of escalation would probably restrain the Communists.”[26] In a memorandum (28 July 1964), McCone informed Johnson that:

In response to the first or second categories of action, [the] local Communist military forces in the areas of actual attack would react vigorously, but, we believe, that none of the Communist powers involved would respond with major military moves designed to change the nature of the conflict . . . [That] air strikes on North Vietnam itself (Category 3) would evoke sharper Communist reactions than [would] air strikes confined to targets in Laos, but, even in this case, [the] fear of escalation would probably restrain the Communists from a major military response. . . .[26]

Soon after the Gulf of Tonkin incident (2 August 1964), in a memorandum (8 September 1964) the National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy (r. 1961–1966) advised Pres. Johnson to cease military provocations of North Vietnam until after October, when the government of the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) would be properly manned, fitted, and kitted to fight an anti–Communist war against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV):

The main further question is the extent to which we should add elements to the above actions [of secret warfare] that would tend, deliberately, to provoke a DRV reaction, and consequent retaliation by us.

Examples of actions to be considered were running US naval patrols increasingly close to the North Vietnamese coast and/or [sic] associating them with [the] 34A operations.

We believe such deliberately provocative elements should not be added, in the immediate future, while the GVN is still struggling to its feet. By early October, however, we may recommend such actions, depending on GVN progress and Communist reaction in the meantime, especially to US naval patrols.[27]

Leak

Leaked secrets

As one of the authors of the Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force (The Pentagon Papers), the analyst Daniel Ellsberg had access to the historical work at the RAND corporation.[14] Having become an opponent of the US war against Vietnam, Ellsberg and fellow researcher Anthony Russo photocopied parts of the Report in October 1969 in order to publish the document to the American public,[28] which action Ellsberg decided upon failing to interest Henry Kissinger, the president’s NSA advisor (r. 1969–1975), and senators William Fulbright and George McGovern, in the historical facts indicated and reported in The Pentagon Papers.[14]

Likewise, Ellsberg had shown some documents from the Report to the politically sympathetic policy experts Marcus Raskin and Ralph Stavins of the Institute for Policy Studies, both of whom refused to publish the documents,[29][30] but recommended that Ellsberg communicate with the reporter Neil Sheehan of The New York Times whom Ellsberg had earlier met in Vietnam.[31][30] In the event, on 2 March 1971, the government analyst Ellsberg leaked 43 volumes of the Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force to the reporter Sheehan for subsequent publication as The Pentagon Papers (1971) in The New York Times newspaper.[32]

Leaked secrets published

Having received the leaked Report documents from Daniel Ellsberg, the reporter Neil Sheehan made work copies for the editors A. M. Rosenthal and James L. Greenfield, the deputy editors for foreign news Gerald Gold and Allan M. Siegal, and for the three newswriters Fox Butterfield, Hedrick Smith, and E. W. Kenworthy, who were to write a publishable summary of Ellsberg’s leaked documents;[33][31] and a copy to Max Frankel, the Washington, D.C. bureau chief for The New York Times.[34][35][36]

About the legality of publishing excerpts from a secret government document (Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force) leaked by the government employee Daniel Ellsberg, the newspaper’s external legal counsel, Lord Day & Lord, advised against publication,[14] but the in-house legal counsel, James Goodale, advised for publication because The New York Times newspaper had a First Amendment right to publish The Pentagon Papers — government documents about the US foreign policy meant to provoke a war between the US and North Vietnam.[31] On 13 June 1971, The New York Times began piecemeal publication of The Pentagon Papers; the first news article was titled “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces Three Decades of Growing US Involvement.”[14][37]

Congress responds

To ensure public debate of the anti–Communist foreign policy for the geopolitical Containment of Communist China that is reported in The Pentagon Papers, on 29 June 1971, US senator Mike Gravel recorded to the Congressional Record 4,100 pages of The Pentagon Papers, which were in possession of Gravel’s Subcommittee on Public Buildings and Grounds. To the Congressional Record, Sen. Gravel recorded passages from The Pentagon Papers that were edited by academics, the historian Howard Zinn and the linguistics profr. Noam Chomsky.[38][39] In the event, the Nixon government ordered a federal grand jury to investigate the illegality of leaking The Pentagon Papers to the American press. To that federal grand jury, an aide of Sen. Gravel, Leonard Rodberg, testified about his participation in the publication of the Pentagon Papers. Moreover, in the senatorial free-speech case of Gravel v. United States (1972), Sen. Gravel asked that the subpoena be voided because of the senatorial protections provided by the Speech or Debate Clause in Article I, Section 6 of the US Constitution.

The Nixon government acts

Upon publication of The Pentagon Papers in March 1971, the Nixon government (1968–1974) did not act to suppress the leaking of the secret history of the US in Vietnam, because the historical facts (diplomatic, political, military) embarrassed the Kennedy government (1961–1963) and the Johnson government (1963–1969); however, as the national security advisor, Henry Kissinger (r. 1969–1975) recommended to Pres. Nixon that the Department of Justice promptly prosecute the whistle-blower who leaked of The Pentagon Papers and so publicly establish that the Nixon government would prosecute every illegal publication of government documents.[14]

The legal argument of the Nixon government’s espionage prosecution was that, as employees of the federal government, the policy analyst and historian Daniel Ellsberg and the editorial researcher Anthony Russo were guilty of a felony crime, as defined in the Espionage Act of 1917, because neither man had the authority to publish secret government documents.[40] After the publication of three newspaper articles derived from The Pentagon Papers, US Attorney General John N. Mitchell (r. 1969–1972) attempted, but failed, to persuade the New York Times Corporation to voluntarily cease publishing the Papers on 14 June 1972;[14] afterwards, Atty. Gen. Mitchell used a federal court injunction to compel The New York Times newspaper to (temporarily) cease publishing The Pentagon Papers; [14][41] the newspaper’s publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger said:

These [government] papers, as our editorial said this morning, were really a part of [a foreign policy] history that should have been made available considerably longer ago. I just didn’t feel there was any breach of national security, in the sense that we were giving secrets to the enemy.[42]

In the event, the free-speech lawsuit New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) thwarted the legal efforts of the Nixon government to halt the publication of The Pentagon Papers (a summary of the Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force) because said action of publication, distribution, and communication endangered the national security of the US.[43]

On 18 June 1971, The Washington Post newspaper published articles based upon The Pentagon Papers, and the Assistant U.S. Attorney General William Rehnquist officially asked The Washington Post to cease their publication of The Pentagon Papers; upon the newspaper’s refusal to cease and desist, Rehnquist sought, but failed to obtain, an injunction from a US district court.[14] To wit, Judge Murray Gurfein refused to issue the injunction requested by Rehnquist because:

“The security of the Nation is not at the ramparts alone. Security also lies in the value of our free institutions. A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in [government] authority to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.”[44]

The Nixon government appealed Judge Gurfein’s decision, and, on 26 June 1971, the US Supreme Court heard assistant US attorney Rehnquist’s anti-publication arguments against The Washington Post and against The New York Times,[43] despite the fact that fifteen other newspapers had received and published copies of The Pentagon Papers.[14]

The Supreme Court acts

On 30 June 1971, the US Supreme Court decided, 6–3, that the Nixon government had failed to meet the legal burden of proof required for a prior restraint injunction that would allow the US federal government to censor newspapers. Among the nine different legal opinions about the publication and censorship of The Pentagon Papers, concerning the case of New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971), judge Hugo Black said that:

Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.

— Justice Black[45]

In the US of the 1970s, despite the Supreme Court having thwarted the US federal government's censorship of newspapers — by manipulating the legal and the court systems — to halt the publication of The Pentagon Papers, the editorial community of reporters and newspaper editors then knew that:

As the press rooms of the Times and the Post began to hum to the lifting of the censorship order, the journalists of America pondered with grave concern the fact that for fifteen days the 'free press' of the nation had been prevented from publishing an important document and for their troubles had been given an inconclusive and uninspiring 'burden-of-proof' decision by a sharply divided Supreme Court. There was relief, but no great rejoicing, in the editorial offices of America's publishers and broadcasters.

— Freedom of Speech in the United States, pp. 225–226.[46]

Ellsberg and Russo on trial

In March 1972, at a hearing before the Boston Federal District Court, asst. profr. of government at Harvard, Samuel L. Popkin, was found in contempt of court and subsequently jailed for a week for having refused to answer the questions of a grand jury who were investigating the case of The Pentagon Papers. In the legal aftermath, the Faculty Council of Harvard College passed a resolution condemning the Nixon government's public interrogation of school teachers over political and legal arguments that justify “an unlimited right of grand juries to ask any question and to expose a witness to citations for contempt [of court] could easily threaten scholarly research”.[47]

On 28 June, at the U.S. Attorney's office in Boston, Mass.,[48] the policy analyst and historian Daniel Ellsberg admitted to having leaked The Pentagon Papers to the press: “I felt that, as an American citizen, as a responsible citizen, I could no longer cooperate in concealing this information from the American public. I did this clearly at my own jeopardy and I am prepared to answer to all the consequences of this decision.”[42]

Consequently, in Los Angeles, Calif., with authority from the Espionage Act (1917), a grand jury formally charged Daniel Ellsberg and his editorial researcher Anthony Russo with stealing and holding federal secret documents;[42] however, on 11 May 1973, Federal District Judge William Matthew Byrne, Jr. declared a mistrial and dismissed all of the criminal charges against Ellsberg and Russo, after the Court learned that the Nixon government had earlier ordered the White House Plumbers to break-and-enter into the medical office of the psychiatrist of Daniel Ellsberg to steal his psychiatric and medical files. To thwart judge Byrne's anti-government declaration of mistrial, the Nixon government then offered the directorship of the FBI to judge Byrne.

The legal flaws of the Nixon government's prosecution of the government employee Ellsberg included the prosecutor's claim of the government having lost the (illegal evidence) wire-tap recordings of Ellsberg's conversations, recorded by the White House Plumbers, for which legal misconduct judge Byrne ruled that: “The totality of the circumstances of this case, which I have only briefly sketched, offend a sense of justice. The bizarre events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case.” Despite judge Byrne's mistrial ruling having freed Ellsberg and Russo, although neither man was acquitted of his criminal violations of the Espionage Act of 1917.[14]

Full publication

Concerning the editions of The Pentagon Papers, project participant Leslie H. Gelb said that The New York Times published about five percent of the 7,000-page Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force initially commissioned by secretary of defense Robert McNamara in 1967. That the Beacon Press edition of The Pentagon Papers also was textually incomplete. As the defense department employee who originally classified the Report as “Secret” until 2011, Morton Halperin obtained most of the unpublished texts though the Freedom of Information Act. The University of Texas published an edition of The Pentagon Papers in 1983. The National Security Archive published the remaining portions in 2002.[14]

In 2011, the National Archives and Records Administration announced that full text of The Pentagon Papers would be declassified and published.[49][50] The publication and distribution of the full-text edition of The Pentagon Papers includes the Nixon, the Kennedy, and the Johnson presidential libraries, and the archives in Maryland.[51]

The full release was coordinated by the Archives's National Declassification Center (NDC) as a special project to mark the anniversary of the report.[52] There were still eleven words that the agencies having classification control over the material wanted to redact, and the NDC worked with them, successfully, to prevent that redaction.[52] It is unknown which 11 words were at issue and the government has declined requests to identify them, but the issue was made moot when it was pointed out that those words had already been made public, in a version of the documents released by the House Armed Services Committee in 1972.[53] The NARA published each volume of the Pentagon Papers in separate PDFs,[52] available on their website.[54]

Impact

The Pentagon Papers revealed that the United States had expanded its war with the bombing of Cambodia and Laos, coastal raids on North Vietnam, and Marine Corps attacks, none of which had been reported by the American media.[55] The most damaging revelations in the papers revealed that four administrations (Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson) had misled the public regarding their intentions. For example, the Eisenhower administration actively worked against the Geneva Accords. The Kennedy administration knew of plans to overthrow South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem before his death in the November 1963 coup. Johnson had decided to expand the war while promising "we seek no wider war" during his 1964 presidential campaign,[14] including plans to bomb North Vietnam well before the 1964 United States presidential election. President Johnson had been outspoken against doing so during the election and claimed that his opponent Barry Goldwater was the one that wanted to bomb North Vietnam.[42]

In another example, a memo from the Defense Department under the Johnson Administration listed the reasons for American persistence:

- 70% – To avoid a humiliating U.S. defeat (to our reputation as a guarantor).

- 20% – To keep [South Vietnam] (and the adjacent) territory from Chinese hands.

- 10% – To permit the people [of South Vietnam] to enjoy a better, freer way of life.

- ALSO – To emerge from the crisis without unacceptable taint from methods used.

- NOT – To help a friend, although it would be hard to stay in if asked out.[14][56][57]

Another controversy was that Johnson sent combat troops to Vietnam by July 17, 1965, [citation needed] before pretending to consult his advisors on July 21–27, per the cable stating that "Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance informs McNamara that President had approved 34 Battalion Plan and will try to push through reserve call-up."[58]

In 1988, when that cable was declassified, it revealed "there was a continuing uncertainty as to [Johnson's] final decision, which would have to await Secretary McNamara's recommendation and the views of Congressional leaders, particularly the views of Senator [Richard] Russell."[59]

Nixon's Solicitor General Erwin N. Griswold later called the Pentagon Papers an example of "massive overclassification" with "no trace of a threat to the national security". The Pentagon Papers' publication had little or no effect on the ongoing war because they dealt with documents written years before publication.[14]

After the release of the Pentagon Papers, Barry Goldwater said:

During the campaign, President Johnson kept reiterating that he would never send American boys to fight in Vietnam. As I say, he knew at the time that American boys were going to be sent. In fact, I knew about ten days before the Republican Convention. You see I was being called a trigger-happy, warmonger, bomb happy, and all the time Johnson was saying, he would never send American boys, I knew damn well he would.[42]

Senator Birch Bayh, who thought the publishing of the Pentagon Papers was justified, said:

The existence of these documents, and the fact that they said one thing and the people were led to believe something else, is a reason we have a credibility gap today, the reason people don't believe the government. This is the same thing that's been going on over the last two-and-a-half years of this administration. There is a difference between what the President says and what the government actually does, and I have confidence that they are going to make the right decision, if they have all the facts.[42]

In 1991, Les Gelb said the following:

But I cannot say that I was pleased. I worried about the turmoil that would enter my life, then as a scholar at the Brookings Institution. I worried about the potential misuse of the papers by doves to stamp government leaders as liars and by hawks to brand war critics as traitors.

What troubled me was that the papers—a vast, undigested mass of fragmentary truths—in the newspapers would become like sticks of historical dynamite, damaging more than illuminating the ongoing struggle over Vietnam policy.

How publication affected that struggle is still unclear. But then and now and above all, the Times' publication insured what mattered most to those of us who wrote the studies and to our democracy—that the papers would live.[7]

Gelb reflected in 2018 that many people have misunderstood the most important lessons of the Pentagon Papers:

Ellsberg created the myth that what the Papers show is that it all was a bunch of lies... [The truth] is, people actually believed in the war and were ignorant about what could and could not actually be done to do well in that war. That's what you see when you actually read the Papers, as opposed to talk about the Papers...

[M]y first instinct was that if they just hit the papers, people would think this was the definitive history of the war, which they were not, and that people would, would think it was all about lying, rather than beliefs. And look, because we'd never learned that darn lesson about believing our way into these wars, we went into Afghanistan and we went into Iraq...

You know, we get involved in these wars and we don't know a damn thing about those countries, the culture, the history, the politics, people on top and even down below. And, my heavens, these are not wars like World War II and World War I, where you have battalions fighting battalions. These are wars that depend on knowledge of who the people are, with the culture is like. And we jumped into them without knowing. That's the damned essential message of the Pentagon Papers...

I don't deny the lies. I just want [the American people] to understand what the main points really were.

In films and television

Films

- The Pentagon Papers (2003), directed by Rod Holcomb and executive produced by Joshua D. Maurer, is a historical film made for FX, in association with Paramount Television and City Entertainment, about the Pentagon Papers and Daniel Ellsberg's involvement in their publication. The film chronicles Ellsberg's life, beginning with his work for the RAND Corporation, and ending with the day on which his espionage trial was declared a mistrial by a federal court judge. The film starred James Spader as Ellsberg, Paul Giamatti as Russo, Alan Arkin as RAND Corporation president Harry Rowen, and Claire Forlani as Patricia Ellsberg.

- The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers (2009) is an Oscar-nominated documentary film, directed by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith, that follows Ellsberg and explores the events leading up to the publication of the Pentagon Papers.

- The Post (2017) is an historical drama film directed by Steven Spielberg from a script written by Liz Hannah and Josh Singer about the role The Washington Post played in the Pentagon Papers saga. The film stars Tom Hanks as Post editor Ben Bradlee and Meryl Streep as Post publisher Katharine Graham. Daniel Ellsberg is played by Matthew Rhys.

Television

- The Pentagon Papers, Daniel Ellsberg and The Times. PBS. October 4, 2010. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. "On September 13, 2010, The New York Times Community Affairs Department and POV presented a panel discussion on the Pentagon Papers, Daniel Ellsberg, and the Times. The conversation, featuring Daniel Ellsberg, Max Frankel, former The New York Times executive editor, and Adam Liptak, The New York Times Supreme Court reporter, was moderated by Jill Abramson, managing editor of The New York Times" and former Washington bureau chief, marking the 35th anniversary of the Supreme Court ruling.

- Daniel Ellsberg: Secrets – Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. University of California Television (UCTV). August 7, 2008. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021.

See also

- Afghanistan Papers

- "Credibility gap"

- Edward Snowden

- Global surveillance disclosures

- Israeli retaliation leak

- James L. Greenfield

- Operation Popeye — U.S. weather modification operation, revealed in the Pentagon Papers

- United States diplomatic cables leak

- WikiLeaks

- 2023 Pentagon document leaks

References

- ^ "The Pentagon Papers". United Press International (UPI). 1971. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ Sheehan, Neil (June 13, 1971). "Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ "The Watergate Story". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

Watergate prosecutors find a memo addressed to John Ehrlichman describing in detail the plans to burglarize the office of Pentagon Papers defendant Daniel Ellsberg's psychiatrist, The Post reports.

- ^ "Pentagon Papers Charges Are Dismissed; Judge Byrne Frees Ellsberg and Russo, Assails 'Improper Government Conduct'". The New York Times. May 11, 1973. Archived from the original on February 20, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e McNamara 1996, p. 280

- ^ McNamara 1996, p. 256

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gelb, Leslie H. (October 13, 2005). "Remembering the Genesis of The Pentagon Papers". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ Kaufman, Michael T. (October 31, 2001). "Paul C. Warnke, Johnson Pentagon Official Who Questioned Vietnam War, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ Guardia, Mike (November 8, 2021). Danger Forward. Magnum Books. ISBN 978-0-9996443-8-6.

- ^ Prados, John; Porter, Margaret Pratt, eds. (2004). Inside the Pentagon Papers. Modern War Studies (Paperback). ISBN 978-0-7006-1423-3.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (October 1, 2015). "Gen. John Galvin, a NATO Supreme Allied Commander, Dies at 86". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ Rogin, Josh (July 29, 2010). "Holbrooke: I helped write the Pentagon Papers". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on June 26, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Correll, John T. (February 2007). "The Pentagon Papers". Air Force Magazine. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ a b Gladstone, Brooke (January 12, 2018). "What the Press and "The Post" Missed". On the Media (Podcast). WNYC Studios. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019.

- ^ Correll, John T. (February 2007). "The Pentagon Papers" (PDF). Air Force Magazine. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ Vietnam Task Force, Office of the Secretary of Defense (1969). United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967 (The Pentagon Papers), Index (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ "Cover Story: Pentagon Papers: The Secret War". CNN. June 28, 1971. Archived from the original on October 26, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ "The Nation: Pentagon Papers: The Secret War". Time. June 28, 1971. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ John McNaughton (January 27, 1965). "Draft Memorandum by J.T. McNaughton, "Observations About South Vietnam After Khanh's 'Re-Coup'"". Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Robert McNamara (November 3, 1965). "Draft Memorandum From Secretary of Defense McNamara to President Johnson". Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Sheehan, Neil (June 13, 1971). "Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Evolution of the War. Counterinsurgency: The Kennedy Commitments and Programs, 1961" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ Tim Weiner (June 7, 1998). "Lucien Conein, 79, Legendary Cold War Spy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

He [Conein] ran [secret] agents behind the Iron Curtain, in the early 1950s. He was the C.I.A.'s contact with friendly generals in Vietnam, as the long war took shape there. He was the man through whom the United States gave the generals tacit approval as they planned the assassination of South Vietnam's President, Ngo Dinh Diem, in November 1963.

- ^ "The Pentagon Papers, Vol. 2, Chapter 4, "The Overthrow of Ngo Dinh Diem, May–November, 1963"" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e John A. McCone (July 28, 1964). "Probable Communist Reactions to Certain US or US-Sponsored Courses of Action in Vietnam and Laos". Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ McGeorge Bundy (September 8, 1964). "Courses of action for South Vietnam". Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Ellsberg, Daniel (August 7, 2008). "Ellsberg: Remembering Anthony Russo". Antiwar.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ Young, Michael (June 2002). "The Devil and Daniel Ellsberg: From Archetype to Anachronism (review of Wild Man: The Life and Times of Daniel Ellsberg)". Reason. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Italie, Hillel (June 16, 2023). "Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked Pentagon Papers exposing Vietnam War secrets, dies at 92". Associated Press of New York. Archived from the original on June 29, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c Sanger, David E.; Scott, Janny; Harlan, Jennifer; Gallagher, Brian (June 9, 2021). "'We're Going to Publish': An Oral History of the Pentagon Papers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ Chokshi, Niraj (December 20, 2017). "Behind the Race to Publish the Top-Secret Pentagon Papers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ Scott, Janny (January 7, 2021). "How Neil Sheehan Got the Pentagon Papers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ "Max Frankel, Pulitzer Prize winner who led New York Times, dies at 94". The Washington Post. March 23, 2025. Retrieved March 25, 2025.

- ^ Hond, Paul (Spring–Summer 2021). "The Columbia Guide to the Pentagon Papers Case". Columbia University. Retrieved March 23, 2025.

- ^ "New York Times Company records. Max Frankel papers 1955–1995 [bulk 1976-1993]". New York Public Library. Retrieved March 23, 2025.

- ^ "Introduction to the Court Opinion on The New York Times Co. v. United States Case". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on December 4, 2005. Retrieved December 5, 2005.

- ^ Leahy, Michael (September 9, 2007). "Last". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam; Zinn, Howard (eds.). The Pentagon Papers (Senator Gravel ed.). Beacon Press. OCLC 248181.

- ^ "The Pentagon Papers Case". National security Archives, George Washington University. Archived from the original on March 18, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2005.

- ^ United States v. New York Times Co., 328 F. Supp. 324 (S.D.N.Y. 1971), archived from the original.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Pentagon Papers". 1971 Year in Review. United Press International. 1971. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ a b New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971), archived from the original.

- ^ United States v. N.Y. Times Co., 328 F. Supp. 324, 331 (S.D.N.Y. 1971).

- ^ "New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971)". Findlaw. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ Tedford, Thomas L.; Herbeck, Dale A. Freedom of Speech in the United States (5th ed.). Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Meislin, Richard J. (March 22, 1972). "Popkin Faces Jail Sentence In Contempt of Court Case". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013.

- ^ Ellsberg, Daniel (2002). "Chapter 29: Going Underground". Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-03030-9.

- ^ Steven Aftergood (May 2011). "Pentagon Papers to be Officially Released". Federation of American Scientists, Secrecy News. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ Nixon Presidential Historical Materials: Opening of Materials (PDF), 76 FR 27092 (2011-05-10), archived (PDF) from the original on May 5, 2017, retrieved June 3, 2011

- ^ Jason, Ukman; Jaffe, Greg (June 10, 2011). "Pentagon Papers to be declassified at last". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c O'Keefe, Ed (June 13, 2011). "Pentagon Papers released: How they did it". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (July 23, 2011). "Finding the Secret 11 Words". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ National Archives and Records Administration (June 13, 2011). "Pentagon Papers". Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York City: Basic Books. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-465-04195-4.

- ^ Perlstein, Rick (2008). Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-4302-5.

- ^ John McNaughton (March 10, 1965). "Paper Prepared by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs (McNaughton)". Archived from the original on April 5, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Ground Strategy and Force Deployments, 1965–1968: Chronology". The Pentagon Papers. Vol. 4 (Gravel ed.). Boston: Beacon Press. 1971. pp. 277–604. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via Mount Holyoke College.

- ^ Burke, John; Greenstein, Fred (1989). How Presidents Test Reality: Decisions on Vietnam, 1954 and 1965. p. 215.

Works cited

- McNamara, Robert (1996). In Retrospect. Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-76749-7.

Further reading

- The Pentagon Papers: The Defense Department History of United States Decisionmaking on Vietnam. Boston: Beacon Press. 5 vols. "Senator Gravel Edition"; includes documents not included in government version. ISBN 0-8070-0526-6 & ISBN 0-8070-0522-3.

- Neil Sheehan. The Pentagon Papers. New York: Bantam Books (1971). ISBN 0-552-64917-1.

- Daniel Ellsberg. Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. New York: Viking (2002). ISBN 0-670-03030-9.

- "Marcus Raskin: For him, ideas were the seedlings for effective action" (obituary of Marcus Raskin), The Nation, Jan 29. / Feb 5. 2018, pp. 4, 8. Marcus Raskin in 1971, on receiving "from a source (later identified as ... Daniel Ellsberg) 'a mountain of paper' ... that became known as the Pentagon Papers ... [p]lay[ed] his customary catalytic role [and] put Ellsberg in touch with The New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan ... A longtime passionate proponent of nuclear disarmament, [Raskin] would also serve in the 1980s as chair of the SANE / Freeze campaign." (p. 4.)

- Lukas, J. Anthony (December 12, 1971). "After the Pentagon Papers—A Month in the New Life of Daniel Ellsberg". The New York Times. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- Prados, John; Porter, Margaret Pratt, eds. (2004). Inside the Pentagon Papers. Modern War Studies (Paperback). ISBN 978-0-7006-1423-3.

- Sanford J. Ungar. The Papers and the Papers: An Account of the Legal and Political Battle Over the Pentagon Papers. New York: E. P. Dutton (1972). ISBN 978-0525041559

- George C. Herring (ed.) The Pentagon Papers: Abridged Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill (1993). ISBN 0-07-028380-X.

- George C. Herring (ed.) Secret Diplomacy of the Vietnam War: The Negotiating Volumes of the Pentagon Papers (1983).

- James Risen, "The secret History:How Neil Sheehan Really Got the Pentagon Papers" online

External links

- The Pentagon Papers. U.S. National Archives. August 15, 2016. The complete, unredacted report.

- Pentagon Papers (Complete Gravel ed.). mtholyoke.edu. Archived from the original on August 18, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2003. Complete text with supporting documents, maps, and photos.

- "Battle for the Pentagon Papers". Top Secret. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2007. a resource site that supports a currently playing docu-drama about the Pentagon Papers. The site provides historical context, time lines, bibliographical resources, information on discussions with current journalists, and helpful links.

- Gravel, Mike; Ellsberg, Daniel (July 7, 2002). "Special: How the Pentagon Papers Came to Be Published by the Beacon Press". Democracy Now!. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. (audio/video and transcript).

- "Nixon Tapes & Supreme Court Oral Arguments". gwu.edu.

- Holt, Steve (1971). "The Pentagon Papers: A report". WCBS Newsradio 880 (WCBS-AM New York). Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Part of WCBS 880's celebration of 40 years of newsradio.

- Trzop, Allison. Beacon Press & The Pentagon Papers. Beacon Press. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- "The Most Dangerous Man in America: New Documentary Chronicles How Leak of the Pentagon Papers Helped End Vietnam War". Democracy Now!. September 16, 2009.

- Blanton, Thomas S., ed. (June 5, 2001). The Pentagon Papers: Secrets, Lies and Audiotapes (The Nixon Tapes and the Supreme Court Tapes, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 48). Compiled by Prados, John; Meadows, Eddie; Burr, William & Evans, Michael. The National Security Archive at The George Washington University.

- Ellsberg's obituaries in:

- The New York Times: McFadden, Robert D. (June 16, 2023). "Daniel Ellsberg, Who Leaked the Pentagon Papers, Is Dead at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- the Associated Press: Italie, Hillel (June 16, 2023). "Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked Pentagon Papers exposing Vietnam War secrets, dies at 92". Associated Press of New York. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- On the Media episode on the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg and Gelb's roles in them, and the state of Vietnam War reporting: "The Whistleblower Who Changed History - On the Media". WNYC Studios. June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 25, 2023.